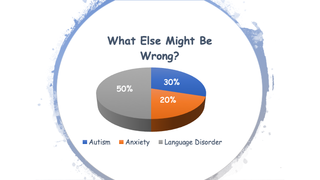

Autism Diagnosis and the Pie Chart Child

Many with autism may have related concerns in need of treatment, too.

Really?

In this post, I will argue that “autism spectrum disorders” (ASDs) are “on the rise” because ASD signs overlap with signs of so many other childhood neurodevelopmental diagnoses.

Several examples:

- A toddler in constant motion, “ASD” might be used rather than “ADHD” (attention deficit hyperactivity disorder), because a toddler is supposedly too young to diagnose with ADHD.

- The early communication failures in ASD can be hard to tell apart from other early receptive or expressive language disorders, wherein there may also be social fallout from not yet talking well when you are expected to be able to say what you want, and what you mean.

- ASD can be a new way to construe symptoms of a child”s anxiety disorder–and that points to an etiology other than an over-anxious parent whom the clinician is not charged with evaluating.

- ASD can be a new, less pejorative way of describing “Intellectual Disability,” not to mention “Oppositional Defiant Disorder” (ODD) or “Disruptive Mood Dysregulation Disorder” (DMDD).

- Children with features of obsessive-compulsive disorder and movement disorders involving symptoms clearly overlapping ASDs may be labeled as having ASD instead.

My “view from the trenches,” directing a very busy autism diagnostic and treatment center, is that too many developmental concerns, “only” get an “autism” label these days. Many, many children we see do have “features” of ASDs but also features of these other neurodevelopmental concerns, too. But when many children get to us, it is only the autism that has been flagged.

Why are these other concerns not getting recognized too (or instead)? Does this mean such children may be getting wrong or incomplete treatment plans? How does this happen?

An editorial last year in the Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry by Dr. Eric Fombonne, a prominent autism epidemiologist highlighted core issues on whether rising prevalence numbers for autism should be understood to inculpate some insidious environmental or infectious processes—or rather, should we be looking to the methodology for identifying cases as contributing to this rise.

He enumerated problems such as counting cases just from medical or educational records, counting cases that are parent- or self-reported, counting cases identified from surveys more likely completed by families living with autism than not, changing DSM diagnostic criteria, and one issue I will focus on now, the lack of “specificity” in what are often referred to as “gold-standard” measures for diagnosing autism.

Specificity: The Bugaboo of Psychiatric Diagnosis

“Specificity” is a statistical term that refers to how unique a symptom is to a disorder. For example, sickled red blood cells are highly specific to the diagnosis of sickle cell anemia. Diagnosis of many other medical disorders have one or more highly “specific” signs or symptoms.

But, signs of autism largely are not “specific.” Instead, almost any single sign of autism also occurs in other neurodevelopmental diagnoses. Autism signs are low “specificity.”

For example:

- Both children with ASDs and with ADHD may have problems knowing when they are talking too loud.

- Young children with ASD and children with language disorders both may use atypical language like echolalia.

- Children with ASDs and children with anxiety disorders often show fear and nervousness around new adults and peers.

- Perhaps a third of children with ASDs have some degree of intellectual disability (ID), and there are signs that can occur in either or both ASD or ID (like over- or under-response to certain sensory inputs).

- With both ASD and ODD, children may appear to lack the ability to respond to social approbation.

- Children with DMRD may be showing early signs of a bipolar disorder (BP) — but early childhood signs leading to BP have not been as well-studied as early signs of autism, and both include poor emotional self-regulation and adaptability.

Important to the point I am making here – and that you may be surprised to learn, is that all these signs and symptoms of both autism and these other conditions I have mentioned are evaluated as part of “gold standard” assessments for autism (including ones a reader may know like the ADOS-2, CARS-2, SRS, and ASRS), but contribute only to confirm the presence of autism—not “rule in” or “rule out” any of the other possible “co-morbid” or “differential” diagnoses I’ve mentioned. This is wrong. We are likely missing other problems we need to be addressing.

Blind Men Feeling the Elephant. In The Politics of Autism, I explain “diagnosis bias” and how it may arise when a clinician meets a new child to determine if he or she has autism: The initial impressions of autism (from the first few moments of meeting the child, from his or her records, from what parents state as concerns, from simply making it through the door of an autism clinic, not to mention reading that the CDC says there’s a 1:59 chance any child has autism) may influence a clinician to interpret all signs of possible autism as confirmation of autism, and not of any of the other conditions in which the same symptoms may be seen.

I call this type of diagnostic bias “blind men feeling the elephant.” Once a hypothesis is formed, it is likely subsequent data will first be used to confirm that hypothesis—rather than forming and testing another. This tendency not only can lead to false-positive diagnoses of autism but may be made more likely to occur in the first place because of what I call “diagnosing for dollars.”

“Diagnosing for Dollars.” Most often, only if a child gets an ASD diagnosis will costly intervention such as 1:1 ABA be deemed “medically necessary” which can compel an insurance company of public health authority to fund it. With a diagnosis of one of the other conditions I’ve enumerated, this is exponentially less likely. In addition, many autism specialty clinics that rely on “gold standard” autism diagnostic measures typically test little (or not at all) for any of these other neurodevelopmental diagnoses, anyway, just for autism–the expensive one to treat. On one level, this might sound fine, but I”m arguing that this should not be the standard of diagnostic assessment. Why?

Pie Chart Children. All of a child”s difficulties deserve attention—not just the ones that can be used to make the case for autism because any or all may require treatment. Many “treatment toolboxes” not just an autism treatment toolbox, may need to be opened.

For example, ABA designed around core autism traits, like low response to social praise and high instrumental drive, may be just the wrong thing for a highly anxious child or an apraxic, language-disordered child. Then, there are some children for whom proceeding on the assumption there even is a primary diagnosis may not be helpful: Parents of such children become increasingly confused and disheartened when one diagnostic assessment after another yields different results. But, if many diagnoses seem apropos—such parents will need to treat what is holding their child back, don”t just get more evaluations hoping finally to divine the one assessment that finally is “right.”

Symptoms, and with it, diagnoses, will change with good treatment. It will always take time and observation of response to intervention to fine-tune both diagnosis and treatment as a child develops.

References

- US Centers for Disease Control (2019). Data and statistics on autism spectrum disorders.

- Fombonne, E (2018). ‘Editorial: The rising prevalence of autism,’ Jnl Ch Psychol & Psychia, 59:7, 717-720.

- Siegel, B (2018). The Politics of Autism, New York: Oxford University Press.